Expanding the Role of Tools in a

Literate Programming Environment

Kent Beck

Ward Cunningham

Tektronix, Inc.

Presented at CASE ‘87, Boston Mass.

Abstract

The tools in a literate programming environment need to accept additional

responsibility to support the programmer's communication with other programmers.

1. The Expanded Role of Programmers

Traditionally, the programmer's role has been to understand a problem

and encode that knowledge in a program a computer can execute. The problem

with this approach is that focusing on the computer as the consumer of

programs leads to programs that are difficult for other programmers to

understand. Maintenance and reusability have emerged as two of the hardest

problems in software engineering, and solutions to both rely on the other

programmers being able to understand a program.

Knuth's Literate Programming [Knut84] [Bent86a] [Bent86b] is one approach

for shifting the programmer's focus to include other humans as code consumers.

A literate program is a literary entity, written to be read from beginning

to end, and taking on the character of a book or essay. Literate programming

expands the role of the programmer to include the responsibility for organizing

a program in such a way that a reader is led naturally to an understanding

of the decisions that shaped the code.

Knuth has created a language, Web, for writing literate programs. A

Web program is a mixture of Pascal, TEX, and Web commands. In addition

to cross referencing, Web includes a macro language, used to avoid Pascal's

problems with forward reference and to allow the programmer to break up

Pascal functions into explainable pieces. To create a literate program

using Web, the programmer must understand Pascal, TEX, and Web, and must

be prepared to deal with errors in any of the languages.

We have been experimenting with a literate programming environment in

Smalltalk-80 [Beck86]. We first built a simple document preparation system,

the Literate Program Browser, which allowed a user to integrate text from

various sources in a document. Initially the sources were code from the

Smalltalk system and explanatory text from the programmer. In this way,

a programmer could annotate the methods in a Smalltalk program to provide

a level of documentation greater than that of embedded comments.

2. Expanding the Role of Tools

The Smalltalk environment includes many tools to help the programmer understand

a program. The browser conveniently organizes the source code of the Smalltalk

system, the inspector lets the user trace the pointer structure of objects,

and the debugger makes visible the dynamic binding of messages to methods

during the execution of a Smalltalk program. In the hands of both novice

and expert users these tools help programmers understand a problem and

create an object-oriented solution. As we have seen above, however, understanding

a problem is only half of the task of the programmer.

Just as the programmer in a literate programming environment takes the

additional responsibility of communicating to other programmers, the tools

in a literate programming environment (or any other programming environment

focused on communicating to both computers and humans) must accept additional

responsibility. In particular, they must be prepared to make the information

they manipulate in a form suitable for inclusion in a document.

In our system, we capture the dynamic behavior of a running program

by initiating an asynchronous interrupt from a function key and indicating

the region of the screen to be saved. This bitmap can then be pasted into

a literate program. In this way the input/output nature of an interactive

program can easily be documented in a document. To describe a menu that

pops up, the programmer pops up the menu and captures the physical appearance

from the screen.

We modified the browser so that it also offers its contents in a form

suitable for inclusion in a document. We added menu items to copy class

and method definitions into a literate program. Importantly, these definitions

are not saved as text, but as pointers into the Smalltalk source code system,

so when a document is printed, the definitions print with their current

value, not just their value on creation.

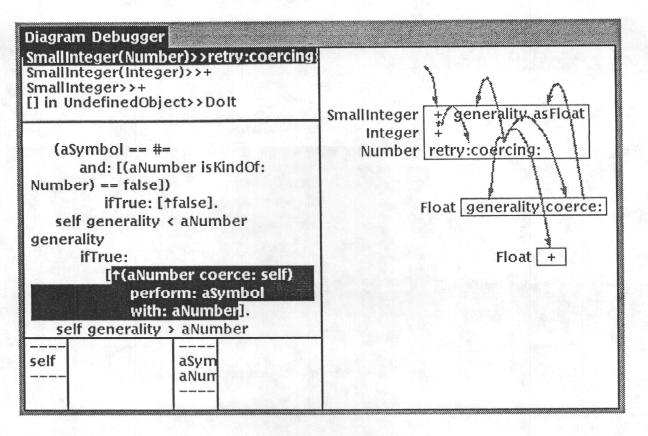

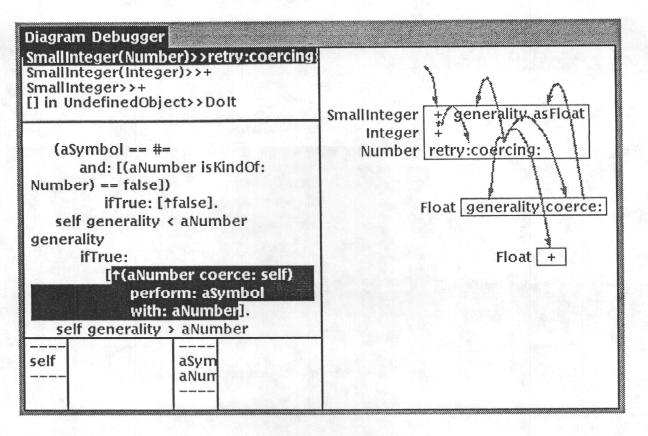

Similarly, we have extended the debugger to make program traces available

for inclusion in a document (see below). An additional pane in the debugger

lets the programmer selectively include message sends in a diagrammatic

representation we have created specifically for object-oriented programs

[Cunn86]. These diagrams can be copied from the debugger and pasted into

a literate program.

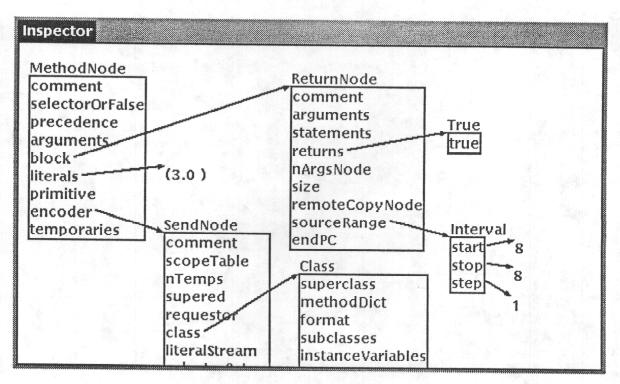

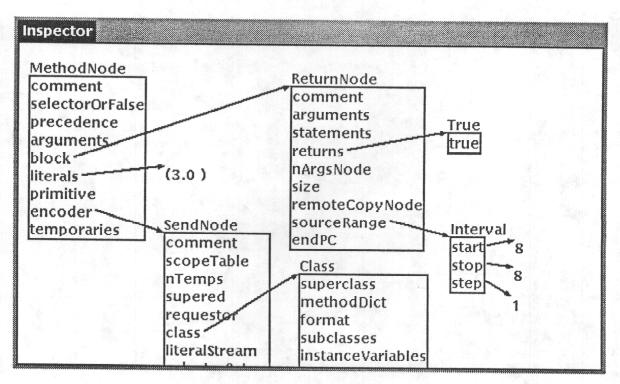

Finally, we have created a new version of the inspector which manipulates

a graphical representation of objects and pointers (see below). An object

displays as a box containing the names of its instance variables and labeled

by the object's class. Pointing to an instance variable in an object causes

the contents of that variable (an object) to be added to the diagram, with

a link from the variable to the object. Objects are uniquely represented

in the diagram, so if an object is referenced several times, all the links

point to the same object.

3. Implementation

We believe the Smalltalk-80 programming environment has aided us immensely

in the creation of a fully literate programming environment. Rather than

having to write all of our tools from scratch we were able to refine existing

tools, making it possible to rapidly experiment with different approaches.

in addition, good Smalltalk code is typically in small (5-7 line) pieces,

about the right size code fragment to include in a literate program, obviating

the need for a macro language.

A tool we built that has helped us many times is a generic graphics

editor It was designed to make creating graphical interfaces just as easy

as creating textual interfaces, and it has made it possible for us to quickly

create graphical representations of various data structures in the system.

In addition, because the generic graphical objects accept the responsibility

of transforming themselves into a form suitable for typesetting, all of

the graphical representations we create inherit the ability to be included

in documents.

Our strategy for printing is to use the MS macros for the troff typesetting

package to produce text. We are working with Apple LaserWriter printers,

so we turn all graphic objects into PostScript, which is embedded in the

troff input postscript provides a powerful set of imaging primitives which

create graphics at printer resolution, but it also manipulates bit-mapped

images so a new graphical object can create a rough but adequate printed

representation by copying an image from the screen.

4. Conclusion

The environment of a programmer who has accepted the responsibility

of communicating with other programmers must support this activity. The

tools in the environment must be prepared to create diagrammatic or textual

representations of the information they manipulate suitable for inclusion

in a document. As the programmer must be prepared to communicate with other

programmers, so, too, must the tools.

References

[Beck86] "The Literate Program Browser", Kent Beck and Ward Cunningham,

Tektronix Technical Report 86-52.

[Bent86a] John Bently and Don Knuth, "Literate Programming," Communications

of the ACM, vol.29, pp.364-369, May 1986.

[Bent86b] John Bently, Don Knuth and Doug McIlroy, "A Literate Program,"

Communications of the ACM, vol.29, pp.471483, June 1986.

[Cunn86] Ward Cunningham and Kent Beck, "A Diagram for Object-Oriented

Programs,” in Proc. ACM Conference on Object-Oriented Programming Systems,

Languages and Applications, Portland, Oregon, 1986.

[Knut84] Donald Knuth, "Literate Programming," Computer Journal, vol.27,

no.2, pp.97-111, May 1984.